[ezcol_1half]In 1935, the Soviet Union conceived an audacious event: a 6,000-mile flight from Moscow to San Francisco.

A successful flight would have been viewed as incredible in 1935. By comparison, Charles Lindbergh’s Atlantic crossing, only eight years before, was 3,600 miles. And Amelia Earhart’s flight from Mexico City to Newark in 1935 was 2,100 miles.

Scott C68

The man chosen for the job was Sigismund Levanevsky, a pioneer Soviet aviator. Levanevsky had been among the first group of people awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. These were the pilots involved in the rescue of the crew of the SS Chelyuskin from the Arctic ice in 1934.

The Chelyuskin was a reinforced steamship. Its mission was to show that a northern route through the Arctic was possible in one season. Chelyuskin made good progress in the summer of 1933, but was trapped in ice in September. Ultimately, it was crushed by the ice and sank. One crew member was killed.

The rest of the crew made it onto the ice. They built a makeshift airstrip, which rescue pilots used in April 1934. It was a heroic operation, conducted in atrocious weather. Ironically, Levanevsky crashed before the operation began, and did not participate in the rescue.

Arctic weather is critical

The San Francisco flight was scheduled for summer, 1935. Arctic weather was expected to be bad, and the Soviets knew that any window of opportunity could close quickly. In fact, it was early August before acceptable weather developed.

Levanevsky and his two crewmembers lifted off from Moscow at just after 6 a.m., Aug. 3. For hours, everything went well. Soviet radio stations issued bulletin after bulletin, reporting the plane’s progress. A stamp (Scott C68) commemorating the flight was issued that day.

New York Times, Page 1; Aug. 4, 1935

The leak was a minor problem. The crew initially planned to fix it quickly and get back into the air. But the Arctic weather quickly worsened. By Aug. 15, the flight had been cancelled.

Levanevsky did not attempt a similar trip until 1937. This time, he used a four-engine Tupolev aircraft with five other men aboard. And he planned to fly only as far as Fairbanks, Alaska.

By this time, the trans-Polar route was becoming old hat. In June 1937, an aircraft commanded by Valery Chkalov had flown from Moscow to Vancouver, Wash. It was the first nonstop trans-Polar flight from Moscow to the United States. The original destination was Oakland, Calif., but it did not make it that far.

Chkalov was exalted by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin as a Hero of the Soviet Union.

Visiting with Shirley Temple

And in July, another crew of three led by Mikhail Gromov flew from Moscow to San Jacinto, Calif., landing in a cow pasture.

The New York Times reported that when “the weary Russians, tottering from fatigue, alighted from their plane to greet startled ranchers, they expressed their immediate needs by flashing little white cards bearing the English words ‘bath,’ ‘eat,’ ‘sleep.’”

Gromov and his crew were taken to Hollywood, where they were shown around a studio by Shirley Temple.

Back in Moscow, Levanevsky took off on Aug. 13. Everything apparently went well for hours. But after crossing the North Pole, the plane reported an engine failure, again due to an oil leak. The plane was capable of flying on three engines, but was handicapped by its huge fuel load.

Hours after the report of engine failure, an Army station in Anchorage, Alaska, intercepted a faint transmission from the plane.

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]“No bearings…having trouble with wave band,” the message said. Parts of the message were unintelligible.

Russian authorities expressed confidence that the plane was on the ice. They marshalled aircraft and icebreakers for a rescue effort.

Pilots also began flying out of Alaska. Among them was Jimmie Mattern, an American who had attempted to circumnavigate the earth in 1933. That effort had ended with a crash in Siberia. Mattern had been rescued by Eskimos and flown to Nome, Alaska, by Levanevsky. Clearly, he felt an obligation to find the Russian in 1937.

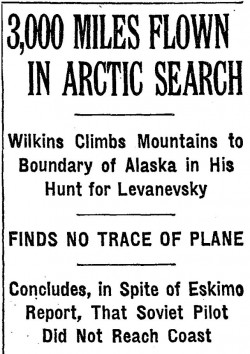

The rescue effort from Alaska was led by Sir Hubert Wilkins, an Australian pilot, photographer and adventurer. Despite flying thousands of miles, he and other pilots saw nothing. Much of the search was hampered by thick clouds as the Arctic weather worsened.

New York Times, Page 41; March 6, 1938

In 1984, a Russian newspaper, Sovetskaya Rossiya, campaigned to have a Siberian lake searched for the aircraft. It reported that in 1965, a Siberian helicopter pilot had found a mound of earth and a slab of wood with Levanevsky’s name carved into it on the shore of a lake named Sebyan-Kyuyel. The report came from Valentin I. Akkuratov, who had participated in the search for Levanevsky in 1937.

Akkuratov believed the plane had drifted off course due to compass problems and the engine failure.

Metallic object indicated

Search parties had reported indications of a large metallic object in the 500-foot-deep lake. Another helicopter reportedly picked up the wooden slab, but the slab supposedly was destroyed when the helicopter crashed. Later search parties could not find the mound of earth. Supposedly, the lake’s shoreline had shifted, wiping out the mound.

The effort at Sebvan-Kyuyel eventually petered out.

In 1999, an Alaskan reported a new find. According to Check-Six.com, a California aviation history Web site:

“In March 1999, Dennis Thurston of the Minerals Management Service in Anchorage noticed an unusual shape on a sonar image of the sea floor during an ARCO pre-drilling survey. In the shallows of Camden Bay, between Prudhoe Bay and Kaktovik, was something shaped like a 60-foot cigar. Thurston thought the cigar looked like the fuselage of an airplane.

“Thurston traveled to Fairbanks for a conference in early May and showed the oddity to David Stone, a professor emeritus at the Geophysical Institute who had searched for the Levanevsky plane years before.

“’When David saw the image, he immediately said “Levanevsky!”’ Thurston said.

“A year later, a submarine search of the site, however, was unable to find any trace of an airplane.”

A long time gone

It has been more than 80 years since Levanevsky and his crew disappeared. Most likely, everyone involved has passed.

Wilkins, the Australian adventurer, went on to serve as a consultant to the U.S. Army from 1942-52. He died in 1958 in Framingham, Mass. In 1959, the submarine USS Skate scattered his ashes at the North Pole.

Just before and during World War II, Jimmie Mattern was a test pilot for Lockheed on the P-38 Lightning. He was diagnosed with a ruptured blood vessel in his brain in 1946, and gave up flying.

Mattern subsequently worked as a real estate agent and ran a travel agency. He died in 1988 at 83.

Valery Chkalov, who reached Vancouver, Wash., in 1937, was killed in a crash in 1938. An impetuous man who disdained authority, he had taken off in a fighter prototype. Chkalov apparently miscalculated his landing, and lost his engine when he attempted to correct. He was 34.

Mikhail Gromov, who landed in the cow pasture near San Jacinto, commanded an air army in World War II. After the war, he was in charge of test flights for the Soviet Air Force. He rose to the rank of colonel general. Gromov died in 1985, age 85.

Sources: New York Times, Wikipedia, Check-Six.com, South Australian Aviation Museum

[/ezcol_1half_end]