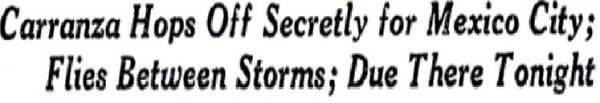

New York Times; Page 1; July 12, 1928

However, when Carranza left New York, he chose to ignore warnings of thunderstorms in the area. His bravery — or foolhardiness — killed him.

Mexico issued six airmail stamps (C5-10) to honor Carranza in 1929, on the anniversary of his death.

It was no accident that Mexico selected Carranza, the great-nephew of the assassinated President Venustiano Carranza, to fly to Washington and New York. Only 22, he already had set records, including flying from San Diego to Mexico City. He looked older than his years because of a crash at age 18. Surgeons had reassembled his face with platinum screws.

His selection made Carranza a national hero. He was known as the “Lindbergh of Mexico.”

The flight to the United States was important news in both countries. Lindbergh had crossed the Atlantic only one year before. The public was fascinated by long-distance flights.

Using a Ryan monoplane similar to Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis, Carranza left Mexico on June 10, 1928, bound for Washington. Early on June 11, he became lost in fog between airmail radio beacons at Salisbury and Mooresville, N.C. He circled Mooresville several times, attempting to get his bearings.

Hearing him overhead, Mooresville motorists drove to Prospect Field. They lined up their cars to illuminate the grass runway with their headlights. The beacon manager fired a red flare to attract Carranza’s attention. He landed safely at 3:45 a.m. and spent several hours at the Commercial Hotel.

Arrival in Washington

The next afternoon, he left for Washington. He was given a hero’s welcome at Bolling Field, where he was met by a group of dignitaries. While in Washington, President Calvin Coolidge hosted a lunch for him. Carranza was hailed for his “nonstop” flight; the landing in Mooresville was glossed over.

Carranza then flew on to New York City. He spent a month there, attending a series of luncheons and other events. Lindbergh spoke at one get-together. Carranza also made a one-day trip to West Point.

In early July, he made preparations to return to Mexico. He was delayed several times by weather. On July 12, he announced that he would not fly. A large crowd that had gathered at Roosevelt Field dis-[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]persed. This was apparently a ruse by Carranza; the unruly crowd could have caused problems on takeoff.

Carranza received a telegram from the U.S. Weather Bureau, and decided to take off. Over New Jersey’s Pine Barrens, he ran into an electrical storm. He was forced down, crashing in the wilderness. A family found his body the next day, and alerted people in nearby Chatsworth. Carranza was identified by the Weather Bureau telegram.

An Army board of inquiry convened at Mount Holly, N.J., to investigate the crash. It concluded that Carranza had attempted a forced landing in the dark, but was unable to avoid trees.

Both nations were stunned. Coolidge offered the battleship U.S.S. Florida to return Carranza’s remains. The offer was refused; Mexico decided to return the body on a train.

The Carranza memorial in Tabernacle Township, N.J. Photo by Daniel D’Auria.

Across the country, people stopped to watch the train pass. When it reached the border, Carranza’s body was transferred to a Mexican train for the trip to Mexico City.

The funeral was held on July 24. The New York Times reported:

“A ten-mile march of 100,000 Mexicans with the body of Captain Emilio Carranza to its tomb overshadowed today all the pageantry of the governments which have mourned his death. It was a stupendous climax to the homeward progress of all that was mortal of the first international flier to die in the midst of his triumph. It was spontaneous, and almost terrible, in its sheer bulk and power.”

Monument raised in New Jersey

A monument was erected to Carranza at the site of the crash, in Tabernacle Township, N.J. Every year, members of the American Legion, along with entourages from Mexican consulates in Philadelphia and New York, gather there to honor Carranza.

A 2009 video describes Carranza’s life and the American Legion’s role in keeping his memory alive. It repeats a story about a phantom telegram ordering Carranza to return home. Here’s what Wikipedia says about the telegram:

“There is a story that on July 12 Carranza received a telegram from Mexican War Minister Joaquín Amaro ordering his immediate return to Mexico City ‘or the quality of your manhood will be in doubt.’ According to the legend, the telegram was found at the crash site in the pocket of the aviator’s flight jacket, but the telegram no longer exists. The story’s proponents do not cite any primary source that confirms the telegram’s existence.”

No contemporary confirmation

Contemporary news accounts do not mention such a telegram. Only the Weather Bureau telegram is included in the news stories. The tale may have been invented to cover the fact that Carranza took off in dangerous weather conditions.

Mexico issued six airmail stamps (C5-10) in 1929, on the first anniversary of Carranza’s death. Five of those stamps (C40-44 and C40a-44a) were overprinted and reissued in 1932 to mark the fourth anniversary.

Sources: New York Times, Wikipedia, Mooresville Tribune

[/ezcol_1half_end]